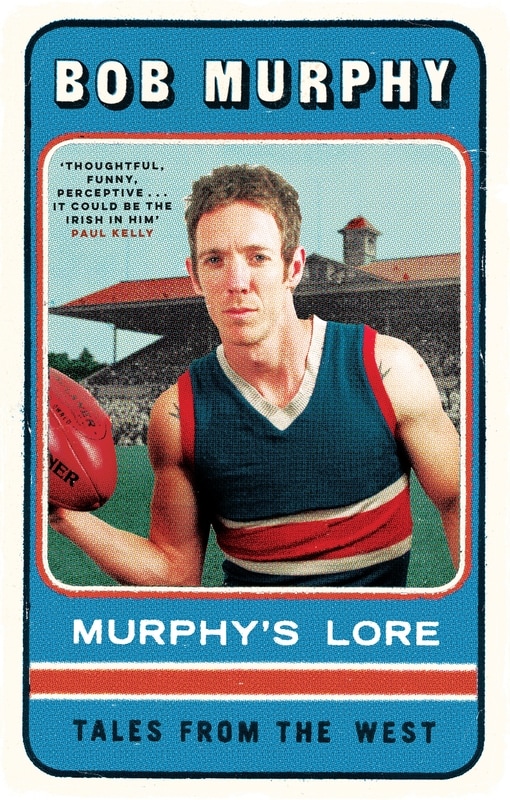

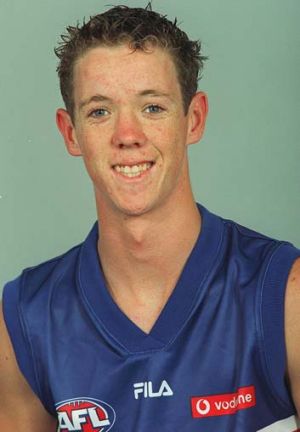

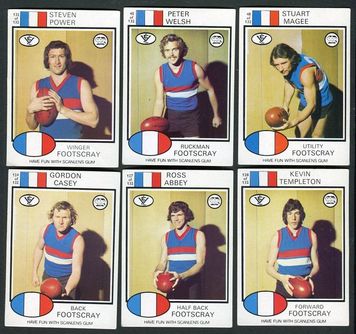

Footy card poses. They’re iconic for fans of a certain age. Baulks with the footy held out like a sacred offering; kicks where the idol’s arms and legs are spread like a launching eagle. They are images footyheads collected in the 1970s, days of limited exposure to sporting heroes. There were no live games on TV. All the games occurred at the same time. Footy players, mostly spoken and written about, retained some mystery. The whole thing was romantic, at least for a kid. Pantomime villains, home grounds with fearsome reputations. Rumours. Nicknames. Characters. Western Bulldogs captain Bob Murphy is only 34, and his footy childhood took place in the 1990s, when games began to spread over the weekend and into the nights, at the ground and live on TV. Footy cards went glossy. But he gets it. Bob bridges the generation gap between the primitive, fabled 1970s – which means just about every footy decade – and the digital present. He also bridges gaps between the bush and the inner city, the learned and the blue collar, the casual fan and the fanatic. The cover of Bob Murphy’s first book Murphy’s Lore features a retro footy card pose. It could be the 1950s. It is apt because Murphy understands the irrational romance of the fan. He is the type of player supporters wish there was more of – a professional who loves his club and loves the game like a fan. Bulldogs fan Andrew Gigacz, contributing editor at australianfootball.com and author of the 2016 Bulldogs premiership chronicle Against The Odds, says Murphy “embraced the club as his life, not just his workplace." "For Bob, it's a passion. And during his early days at Footscray, that passion for the game extended to a passion for the club and its people. “When it comes to footy, he always treats the opposition players with respect... He will praise his opponents and belittle himself rather than the other way around. This endears him to fans of all clubs.” Cats tragic Susie Giese confirms this. "He's just incredibly likeable and very self-deprecating. He's funny, but his humour is never at anyone's expense (except occasionally his own), and he just seems to have his priorities sorted and his head screwed on straight.” Murphy’s eight years of columns for The Age, and his regular TV slot have enhanced his popularity. His Age linkman Peter ‘Tommy’ Hanlon described Murphy’s columns as “enchanting”. They closed the gap “between how we see the game from outside and what it looks like from within”. Hanlon’s final article for The Age was about Murphy. Gigacz says, “Through his columns and media appearances, he's managed to tell stories that are little life observations that most people can identify with, be they be about family, dogs or friends.” His weekly slot on Footy 360 exposed a singular wit who loved a story and a bit of cheek. He instituted a ‘Rascal Of The Week’ segment. Thereby singlehandedly reviving the use of the word rascal. Since his debut in 2000, he’s gone from a geeky stringbean with a shaved head to a wiry veteran with retro sideburns. He looks like a gracefully ageing muso who plays Sunday arvos at a laid-back inner city pub. He loves those pubs and their music – he told Hanlon that he first felt at home in Melbourne when he went to Fitzroy. “Aged 18 and fresh out of Warragul he sat at the bar of the Napier and heard The Rolling Stones' Exile On Main Street for the first time. ‘I asked the barman what it was. Life just took a left turn.’ ” In 2011, his father John told Hanlon, “Rob's always been very conscious about having a life away from football, going to music, his friendships, he's got friendships from primary school. He's maintained all of that, and that's healthy.” That comes across, as Murphy is without pretence. The way Bob plays is as creative as his writing. Slight but lithe, he takes the game on, whether in the middle, back or forward. He weaves through traffic, sees players further afield that no-one else sees. He is quick and brave, making teammates better with his elite link play and silky skills. He’s often good when his team is bad. His form in his first game after a serious knee injury, in round one this year, was astonishing. His Dogs won less of the ball but won because Bob and a couple of others used it so well. “He's a unique man,” his coach Luke Beveridge told us this week, citing his “emotional, empathetic, spiritual side". But Beveridge also reminded us that beneath the good bloke is a fierce competitor. "There is a grunt to him that you don't see… There is that 'put on the war paint' attitude on game day that most of you don't see. His teammates do.” The man himself says "I was a pretty cocky kid. It probably helped. It's been chipped away a little bit. (But) I've always had the belief that I could do it." His modesty can hide his ambition. It was something of a surprise when he took over the Bulldogs leadership in 2015, after one of the club’s lowest ebbs in recent years. But his mum, in 2011, almost predicted it. “He's a questioner, he's a searcher, and so are we. That's good, that's healthy. He's got to believe in the community that he's in at the Bulldogs, he's got to believe in those guys. I think that's the only thing that's going to lift them off the ground. I often want to say to him, 'Just take the young guys out and talk to them, make them feel good'.” Murphy is so good at talking to those ‘young guys’ that rising superstar Marcus Bontempelli wrote this in a remarkably emotional News Corp article: “Bob’s words and presence possess weight. When he says things he means them. One of my greatest football memories is when Bob told me he was proud of me.” It seems ridiculous now that Bob Murphy was not a captain earlier. The year he took over a stricken club, the Bulldogs soared into the finals for the first time in five years, and he was named All-Australian captain. The more responsibility he took on, the better he played. It was unnaturally cruel that such a loyal one-club player should miss out on playing in his club’s long-awaited premiership. It was one of the AFL's most bittersweet moments when the injured Murphy took to the podium last September to celebrate the triumph of his underdog club. But those who think the Dogs used up the footy community's goodwill that day should remember this: If the Dogs make the finals this year, they will be desperate to win it for their captain, their mate, and the most loved player in the league. Yes, Bob Murphy is loved. And you can see why in his footy card pose. Footy on palm, face open to the camera, he is a timeless figure, the accessible good bloke who loves the game. He takes it seriously enough to care, and not so seriously that he can’t laugh at it, and himself. Bob Murphy knows that footy is a game, to be enjoyed. Even if it breaks your heart. Comments are closed.

|